Red Bull Racing & Porsche: The “Sure Thing” Tie-Up That Never Was

Natural Aspiration 09: How - and Why - Christian Horner and Dr. Helmut Marko Outfoxed World’s Most Profitable Automaker on Eve of Historic IPO

Formula 1’s rumor mill, which operates around the clock every day of the year given the vast interest the series commands, is perpetually in need of sustaining grist. A deft paddock operative, often one of the ten Team Principals who serves as their organization’s CEO and primary public spokesperson, can harness the hivemind to their advantage by whispering a few sweet nothings into a trusted reporter’s ear, confident that the unwittingly commandeered mouthpiece will amplify and legitimize whatever twaddle they’re peddling at the moment.

The slickest - perhaps oiliest - Team Principal of all is Christian Horner, the Warwick-educated, Spice Girl-wed, Superman superfan, and member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire who has led Red Bull Racing since its inception, which occurred in 2005 after Austrian energy drink magnate Dietrich Mateschitz purchased the carcass of Jaguar Racing from the Ford Motor Company. Horner is both the longest-serving and youngest Formula 1 team boss. His fans are known as “Hornettes,” apparently.

This year’s worst kept paddock “secret” was the promise of the Volkswagen Group’s (VW) entrance into Formula 1, at long last. Wolfsburg’s various brands had made plenty of noise in the past about joining the circus, but these claims had never amounted to anything concrete.

This time, of course, things were different. In May, Elon Musk groupie Herbert Diess, who was at the time - but no longer - CEO of the VW Group, stated publicly that Audi and Porsche, the Group’s premium brands with sporting heritage and mass appeal, would enter Formula 1 at the next rules cycle, beginning in 2026 (emphasis mine):

Volkswagen's premium brands Audi and Porsche will join Formula One after convincing the German automaking group that the move will bring in more money than it will cost, VW Chief Executive Herbert Diess said on Monday.

Discussions by the board of directors about the two brands' plans had created some divisions, said Diess at an event in Wolfsburg, where the German carmaker is headquartered.

Diess said on Monday that Porsche's preparations for entering Formula One were a little more concrete than Audi's.

Audi is ready to offer around 500 million euros ($556.3 million) for British luxury sports carmaker McLaren as a means to enter, a source told Reuters in March, while Porsche intends to establish a long-term partnership with racing team Red Bull starting in several years' time.

A few months later, at the end of July, a “leak” from an unlikely locale - Morocco, of all places - seemed to confirm the tie-up between Red Bull and Porsche:

While there has been no confirmation of an agreement by either party, a document submitted to Moroccan officials, which is a formality required to green-light the deal by the anti-cartel authorities, was leaked confirming what many had anticipated.

In the document, it is reported that Porsche is looking to acquire 50 percent of Red Bull Technologies, the company that supplies the chassis to both Red Bull and its sister team AlphaTauri. The document also reveals that the partnership will last for a period of ten years.

Meanwhile, Porsche has spent 2022 preparing for its long-awaited IPO, which will see the marque finally moving out from under the purview of the VW overlords who rescued Porsche from financial ruin during the darkest days of the 2008 - 2009 financial crisis; poetically, Porsche had found itself seeking refuge only after attempting an ill-fated takeover of VW. Goliath usually wins, after all.

So, what happened? How - and why - did Porsche receive an embarrassing black eye from the Red Bullies on the eve of the IPO?

Porsche’s Checkered History in Formula 1

Save for Ferrari, of course, Porsche has the greatest motorsport legacy of any automaker. Ferrari began making road cars in 1947, and Porsche kicked off the following year. Porsche has made a few forays into Formula 1 since, but their history in the most rarefied stratum of the sport has been mixed; emphasis on the “checkered” portion of checkered flag.

In the early years of the championship, Formula 1’s rule book changed frequently, and often seemingly by caprice. The 1961 rules permitted 1.5 liter engines, which allowed Porsche’s Formula 2 challenger to compete one rung up the ladder. Porsche took advantage of the opportunity to race its 787 in 1961 and elected to return a year later with a further developed car, the 908. The 1962 season was more successful and saw American Dan Gurney triumph at the French Grand Prix, held at Rouen-Les-Essarts.

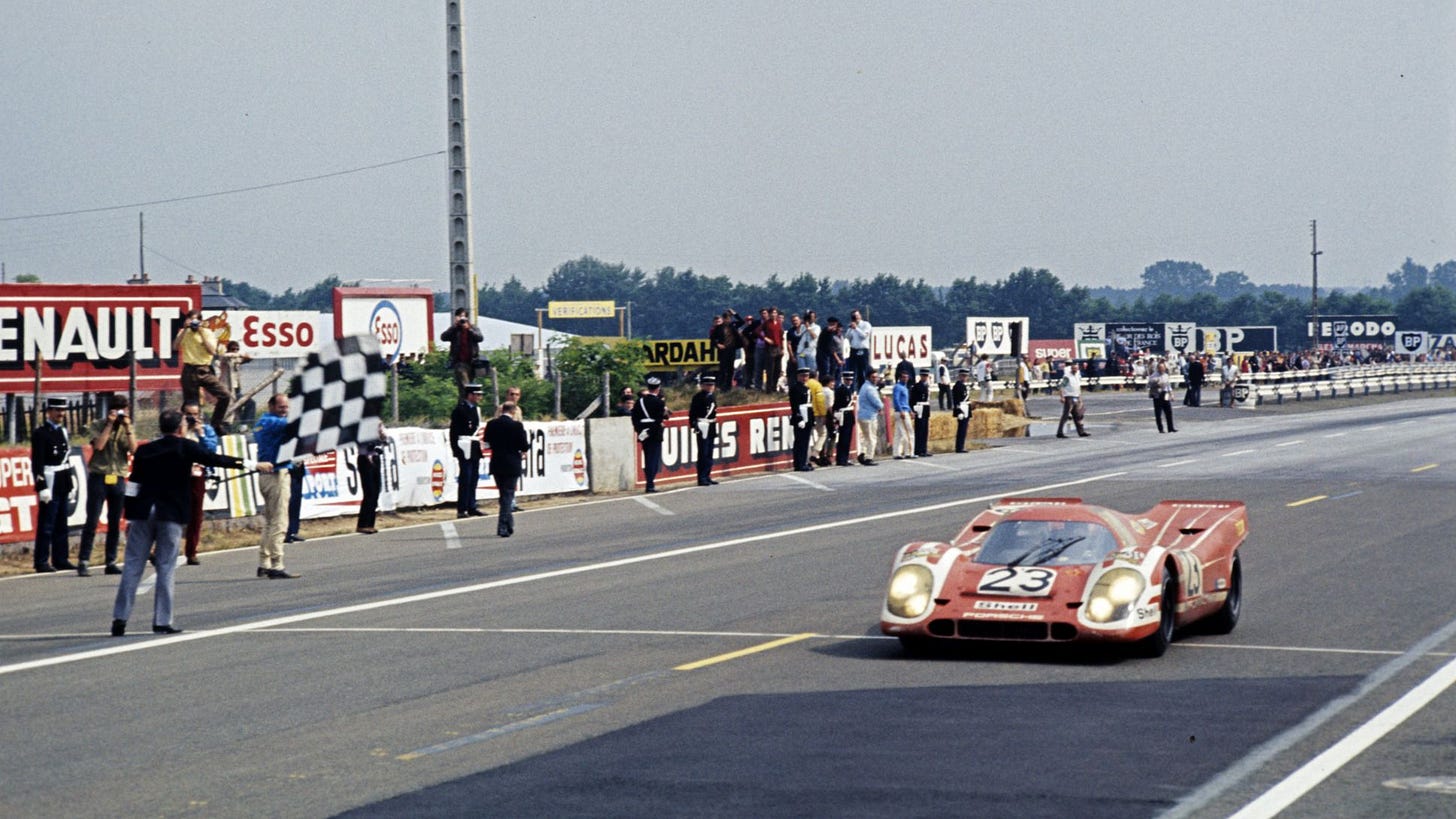

A Porsche chassis powered by a Porsche engine hasn’t won a Formula 1 Grand Prix since; the Germans left Formula 1 at the end of the season and wouldn’t return to elite competition until 1970, when they raced for the first time in the top class at Le Mans.

Porsche emerged from that vintage of the 24 hour race victorious and subsequently found the Circuit de la Sarthe a happy hunting ground - they have since earned 18 additional overall wins at Le Mans.

Porsche was enticed back into Formula 1 in the early 1980s, albeit not in a “works” role. The sport’s first turbocharged era had begun a few years earlier, and it became clear that forced induction would be necessary to compete for wins. Ron Dennis, McLaren’s team boss, persuaded Techniques d’Avant Garde (TAG), the Ojjeh family holding company, to turn its back on the Williams team it had been sponsoring and to fund an engine program for McLaren; Porsche, on the basis of its substantial turbo experience, was selected as the engine building partner for the venture. Interestingly, TAG later went on to purchase the Heuer watch brand in 1985, forming TAG Heuer, which ultimately sold to one of the world’s most odious entities - LVMH. The remainder of the TAG group persisted under the ownership of Mansour Ojjeh, who died in 2021.

The Hans Mezger-designed 1.5 liter V-6 turbo Porsche engines bearing TAG badges powered McLaren to both the World Drivers’ Championship and World Constructors’ Championship in 1984 and 1985. The team also secured the Drivers’ title in 1986, but the Honda-powered Williams team took the Constructors’ crown. Crucially, the Honda effort was a works program - i.e., funded by a manufacturer - and the less lavishly resourced TAG-Porsche axis found itself unable to compete with Honda’s deep pockets. After a disappointing 1987 challenge, Porsche left Formula 1, and Ron Dennis bagged the works Honda engines for McLaren from 1988. The 1988 season proved to be one of the most dominant in series history: Senna and Prost, locked in a bitter intramural battle, won 15 of 16 races for McLaren; but for an errant backmarker who spun into Senna while being lapped at Monza, McLaren would likely have blanked the entire campaign.

Porsche, having spied an opportunity, returned to Formula 1 in 1991. The engine rules had changed in 1989, outlawing turbo power in favor of 3.5 liter naturally aspirated engines of eight-, ten-, or twelve-cylinders. This had not diminished Honda’s dominant position, however: During Porsche’s three-year absence, McLaren-Honda had won both titles in each year.

Even today, Porsche is keen to leverage its past work into new applications. A few quick examples: Porsche’s stillborn 2000 Le Mans prototype eventually lent its (unraced) screaming V-10 to the Carrera GT project; the 2005 RS Spyder’s high-revving, naturally aspirated V-8 developed into the 918’s hybrid engine, and this same powerplant has been further developed into the forthcoming 2023 963 LMDh race car’s engine, although the latest car will feature turbos.

This pragmatism has long pervaded Porsche’s philosophy. Hans Mezger, in a rare misstep, sought to take a pair of his old 1.5 liter V-6 turbos from the McLaren partnership and combine them, creating a V-12. Displacement would be increased to the 3.5 liter limit, and the turbos would be jettisoned, per the rules. Porsche struck a deal to provide engines to the privateer Footwork team. Unfortunately, the engine was both overweight and underpowered, so the Footwork cars were far from fleet. Footwork was so aggrieved that they fired Porsche in the middle of the season! That was the last time that Porsche had any involvement with Formula 1, over 31 years ago.

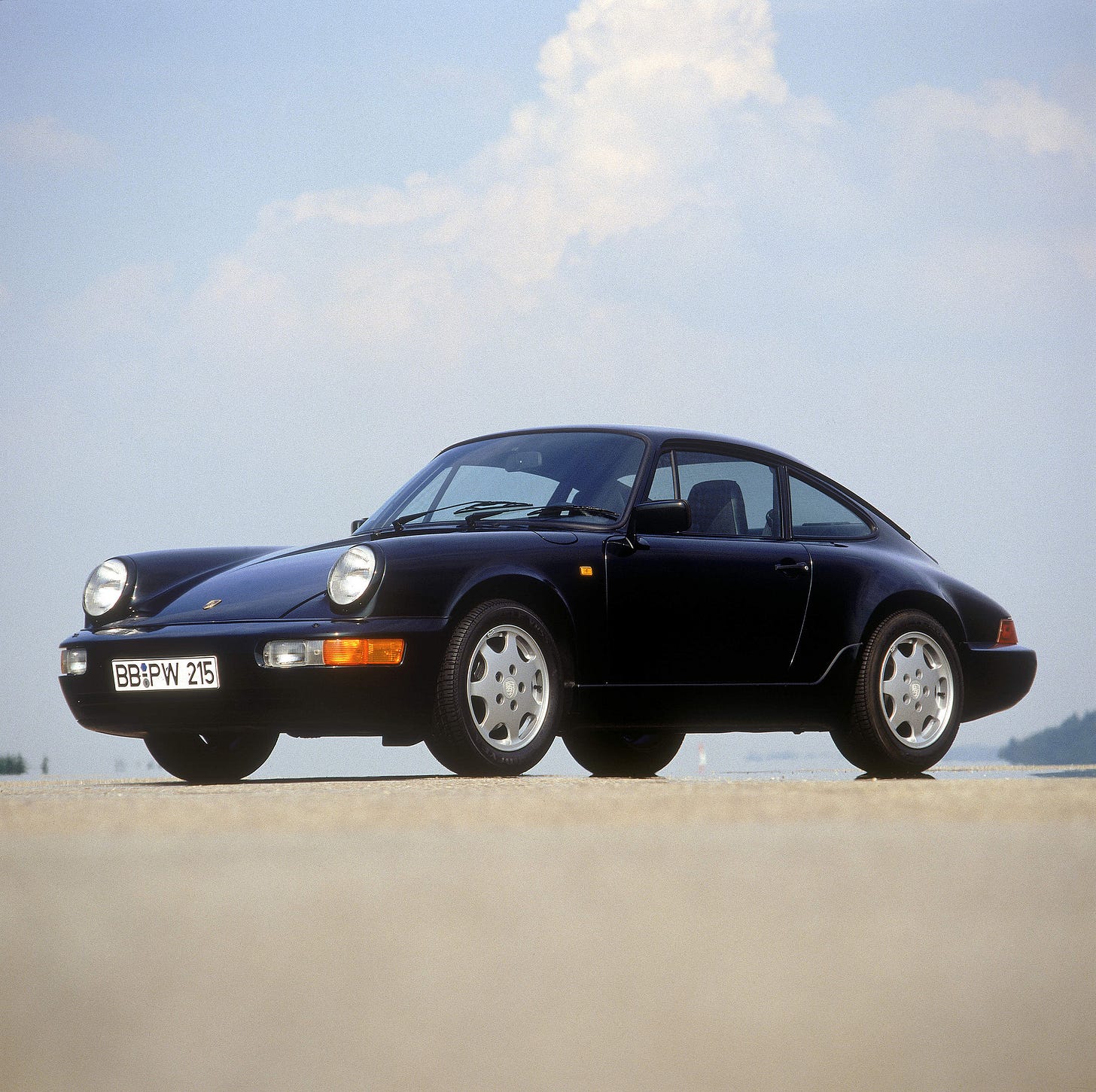

Transforming Porsche from Diminutive Sports Car Company to Swaggering Cash Cow & Hedge Fund

The early 1990s were similarly challenging for Porsche’s road car business. The 964 generation 911, which arrived at the end of the 1980s, had been rather expensive to develop, and the front-engined model portfolio was acutely aged at that point. A strong Deutschmark during that period made exports challenging, further exacerbating the internal problems. While it’s commonly believed that the “engineered up to a standard, rather than down to a cost” ethos characterized Porsche through the end of the air-cooled era, the final such model - the 993 generation 911, debuting in 1995 - was somewhat cheaper to build versus its immediate predecessor, a fact reflected by Porsche lowering the suggested price of the 993. Can you imagine Porsche lowering prices today? Further, Porsche had hoped to modernize the 993’s interior, but the swansong air-cooled effort retained the dated yet classic aesthetic inside; the “improved” interior had to wait for the all-new, water-cooled 996 generation 911. Mercifully.

Porsche, inspired by the efficiencies that Toyota could extract from its own products, took the cost rationalization overboard with the 996 and its sibling, the 986 generation Boxster. Although the contemporary reviews were buoyant - I still remember reading Road & Track’s purple prose after the launch drive - customers were disappointed by a litany of issues, chiefly the poor overall build quality, cheap interiors, and fragile engines. The 996 and 986 did, however, provide Porsche some financial breathing room. It was the next vehicle that transformed Porsche’s fortunes.

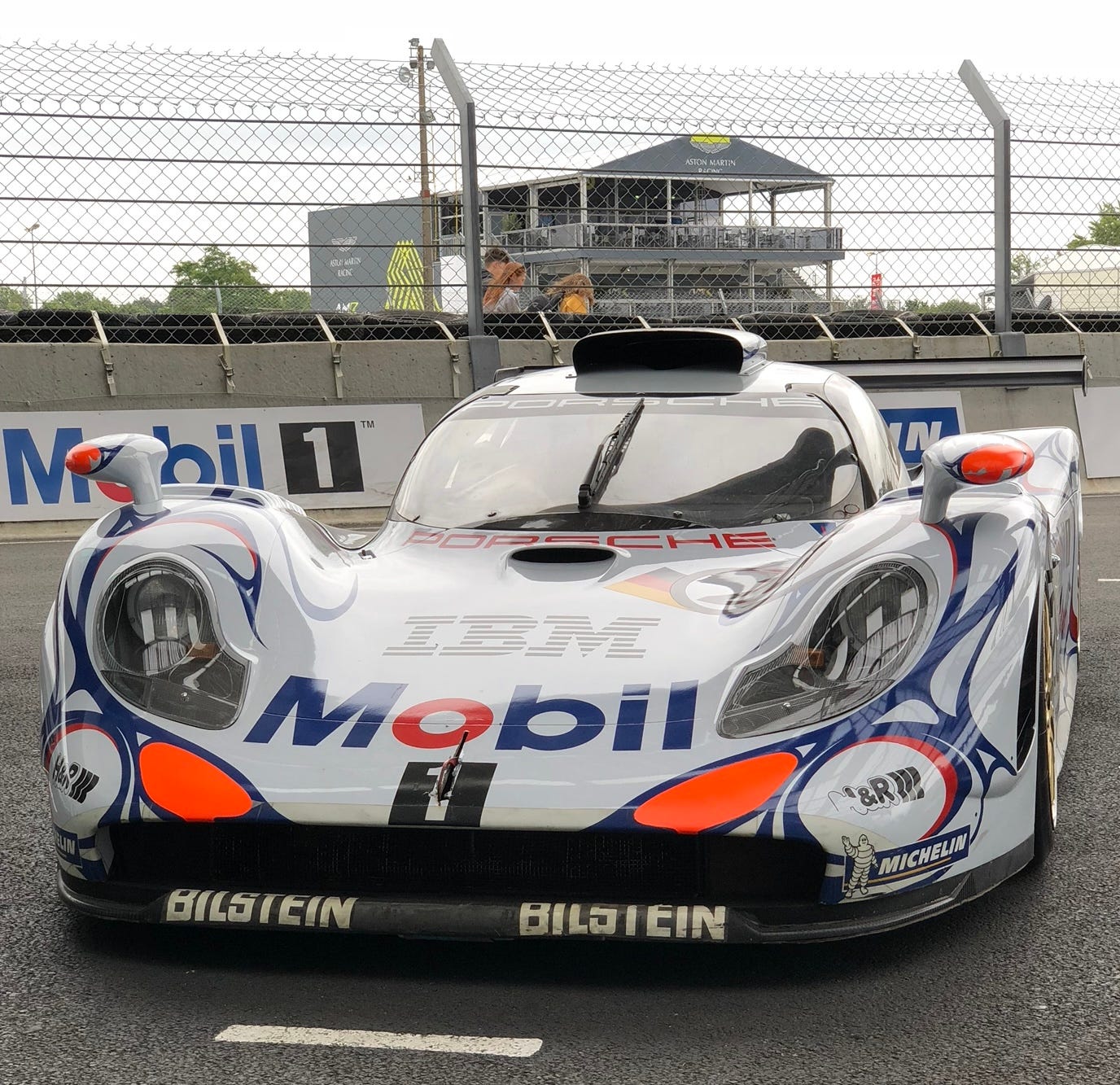

Despite the challenges that the road car business faced during the 1990s, Porsche continued to race at Le Mans. The mutability of the Le Mans regulations, which are controlled by the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO), make the Formula 1 rulebook appear evergreen: Le Mans - and all of the other sports car series that take their marching orders in one way or another from the ACO - is characterized by boom and bust. Manufacturers come and go, but Porsche has (usually) remained constant. The 24 hour race found itself ascendant in the middle of the decade. The GT1 class of cars, which were ostensibly based on “road cars,” vied with purebred prototypes for overall victory. The GT1 cars were extravagantly styled and captivated public interest; indeed, they still do. The McLaren F1 GTR, which was legitimately road car-based, triumphed overall in 1995. In response, Porsche rolled into La Sarthe the next year with a race car - the 911 GT1 - from which it had subsequently developed a “road car,” thereby homologating the 911 GT1 but perverting the spirit of the rules.

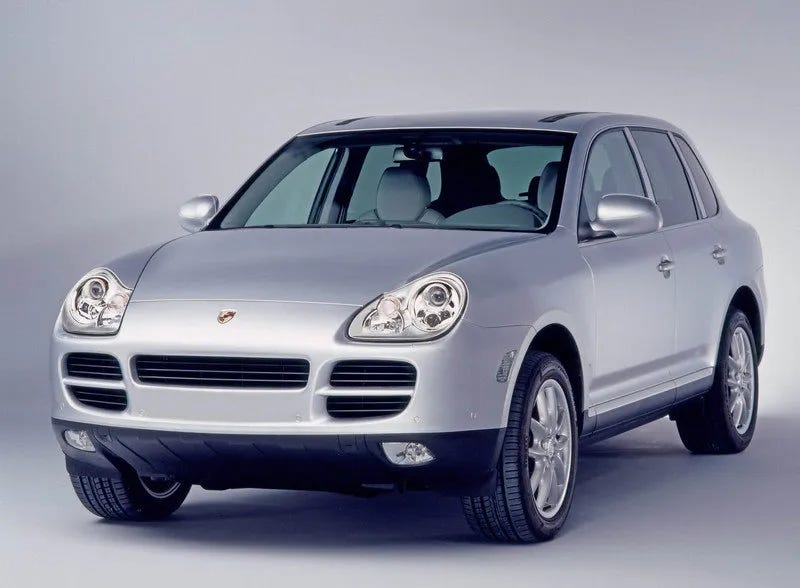

Porsche would have to wait until 1998 to earn an overall victory with a GT1 car, which came courtesy of the 911 GT1-98, the final iteration of the 911 GT1 lineage and perhaps the most beautiful race car ever created. The wait was worth it, for it was a memorable Porsche 1-2 - the 16th overall victory at La Sarthe - achieved in Porsche’s 50th anniversary year. By 1998, Porsche had the aforementioned LMP2000 open-top prototype under clandestine development in anticipation of the post-GT1 era, but Stuttgart announced that it would pull the plug on top class Le Mans competition to … focus on developing an SUV.

Enter the Cayenne. Although BMW had beaten Porsche to market with its X5, Porsche wanted a slice of the extremely profitable premium sporty SUV segment and had had the Cayenne on the drafting board as early as 1998; the production model debuted for the 2003 model year. The brand purists, after having endured the switch to water-cooled propulsion in the 911 and the arrival of the down-market Boxster, were apoplectic. Porsche disregarded their whining and went on to develop a series of passenger cars: Panamera; Macan; Taycan. These vehicles have facilitated Porsche’s transformation from financially imperiled sports car maker - for several years in the mid-90s, the 993 generation 911 was the only vehicle Porsche produced - into the world’s most profitable (volume) automaker.

The Cayenne filled Porsche’s coffers to bursting. Rather than use this good fortune to return to top-level factory competition in Porsche’s adopted spiritual home in Western France, Wendelin Wiedeking - Porsche’s then-CEO - decided to moonlight as a hedge fund; here’s a timeline of events:

9/25/05 - Porsche announced intention to purchase a 20.0% stake in VW.

9/28/05 - Porsche disclosed 10.3% voting stake in VW.

11/15/05 - Porsche Supervisory Board authorized plan to increase VW ownership to 29.9%.

4/30/07 - Porsche submitted “mandatory” takeover offer after disclosing VW ownership in excess of 30.0%.

3/14/08 - Bear Stearns collapsed.

4/3/08 - Porsche Supervisory Board authorized plan to increase VW ownership to greater than 50.0%.

9/15/08 - Lehman Brothers failed.

10/26/08 - Porsche announced it held stock and options providing control of 74.0% of VW’s voting shares; amid financial crisis in post-Lehman fallout, short sellers had gone short against VW’s stock, which had risen in a troubled market due to Porsche’s buying. Upon announcement, short sellers were “squeezed,” and the flurry of short covering - i.e., buying - briefly made VW the most valuable company in the world.

5/6/09 - Porsche announced plan to pivot away from VW acquisition and instead “merge” with VW. VW Chairman Ferdinand Piëch cautioned that Porsche must de-leverage in advance of any transaction; Porsche had borrowed ~€9 billion to purchase VW shares, planning to use VW’s balance sheet to repay the loans post-acquisition.

5/25/09 - Porsche received €700 million loan from VW.

7/10/09 - Porsche Chairman Wolfgang Porsche, Piëch‘s cousin, called for Supervisory Board meeting to discuss possible capital raise; plan was to sell €5 billion stake to Qatar Investment Authority.

7/23/09 - Porsche Supervisory Board approved plans for €5 billion Qatar capital raise. CEO Wendelin Wiedeking fired.

12/7/09 - VW announced it had purchased 49.9% of Porsche for €3.9 billion, implying a total value of ~€7.8 billion; Porsche and Piech families owned 30.0% of Porsche; Lower Saxony - the state in which Wolfsburg is located - owned 20.1%.

In July of 2012, VW agreed to purchase the outstanding stake - 50.1% of the company - from the families and Lower Saxony for ~€4.5 billion, implying a total value of ~€9.0 billion. Lower Saxony currently owns 11.8% of VW and has a 20.0% voting stake. At that point, Porsche AG - the manufacturer - was wholly owned by VW; Porsche SE - the holding entity controlled by the Porsche and Piëch heirs - was VW’s largest shareholder and held majority voting rights.

Return to Le Mans & Dieselgate Scandal

In 2011, the ACO announced a new set of rules for the LMP1 class at Le Mans, which was set to feature complex hybrids and a relatively open rule book that would allow a variety of competitive philosophies: Petrol versus diesel; natural aspiration versus forced induction; battery versus flywheel vs supercapacitor. Enticed by the opportunity to compete on this technological stage, Porsche announced its intention to return to Le Mans, the centerpiece of the World Endurance Championship (WEC), in 2014. While Porsche had been away for 16 years, Audi had established itself as the new benchmark at Le Mans; Ingolstadt won during 12 of those years and achieved their 13th - and final, to date - victory in 2014, although Porsche’s new 919 hybrid ran competitively during its first race. Porsche returned in 2015 with a three-car assault and won both Le Mans and the WEC title; they repeated the same feat in both 2016 and 2017, for a hat trick each of Le Mans victories and WEC titles.

Audi bowed out of LMP1 at the end of 2016, and Porsche followed suit a year later. There was much speculation about the German brands’ motivations to leave LMP1 racing. While it was true that Porsche and Audi were spending serious cash - perhaps enough combined to fund a Formula 1 effort - to compete in an intra-VW battle at the sharp end of the grid (Toyota was rarely able to hang with the Germans and Nissan raced its embarrassingly slow challenger only once, at Le Mans in 2015), the real culprit was the Dieselgate scandal.

In brief, the Dieselgate scandal came to light in 2015 after the US Environmental Protection Agency uncovered that VW had incorporated a software cheat into its diesel engines. The software allowed the impacted vehicles - roughly 11 million vehicles delivered worldwide from 2009 to 2015, of which ~500,000 were delivered to the US - to detect when they were being subjected to emissions testing and deploy a special engine map that allowed them to understate their real-world emissions. In reality, the impacted vehicles emitted up to 40x greater NOx than what the testing measured. This perfidious plan impacted cars throughout VW’s brand portfolio, including Audi and Porsche.

Punishment was swift and severe. Massive fines piled up, and several leading executives faced criminal charges, including former Porsche Motorsport boss Wolfgang Hatz.

Chastened, VW announced in 2019 that it would discontinue combustion-engined racing programs; this proviso applied only to the VW brand itself, however.

Formula (m)E(h)

In a move perhaps reminiscent of U2’s claim that they had to “go away and dream it all up again” between The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby albums, both Audi and Porsche announced that they would enter Formula E in the wake of their respective LMP1 departures.

Formula E is a nascent electric car racing series that has attracted significant interest from carmakers despite the facts that the series has essentially zero fan following and that the racing isn’t particularly entertaining. I attended one Formula E race weekend - the 2018 Brooklyn, New York event - and literally feel asleep during the race on Saturday afternoon. Although I had been gifted a $2,000 Audi VIP hospitality ticket, I elected to skip the Sunday race and instead work from a charmless office building in Midtown Manhattan.

What made Formula E so attractive for OEMs?

Relatively low cost of entry; Formula E is a spec series on the chassis side (like IndyCar).

Opportunity to compete - and hopefully win - against numerous peer brands.

Greenwashing in a post-Dieselgate world.

Marketing tie-in for new and forthcoming EVs.

Consequently, Porsche found itself competing in Formula E against the “Big Three” - Audi, BMW, and Mercedes - from the Fatherland. Yet just as quickly as they rushed in, the other German brands have rushed back out, leaving Porsche to compete with a slate of less prestigious carmakers and independent teams. Unfortunately, Porsche isn’t as competitive as they’d like to be, even against a diminished field: Porsche has raced for three seasons, comprised of 42 races representing 84 total starts. They have managed to win precisely once.

Renewed Interest in Formula 1

Despite the damning performance in Formula E, Porsche decided that they’d like to return to Formula 1. Audi felt the same way and will be racing in Formula 1 beginning in 2026.

What made Formula 1 so attractive?

When Liberty Media completed their purchase of Formula 1’s commercial rights in 2017, they set about transforming Bernie Ecclestone’s ossified operation. Bernie had actively disdained youthful audiences, reasoning that the presence of, for example, trackside Rolex advertising was of little concern to those without the budget for luxury timepieces. Just five years ago, Formula 1 had scarcely any social media activity, and there was no official YouTube channel. Moreover, Bernie went so far as to threaten legal action against drivers who posted their onboard footage to social media!

The virtuous flywheel of a vastly enhanced social media presence, the sensational Drive to Survive program on Netflix, the wave of which crested at the optimal time during pandemic-era lockdowns, and a new generation of compelling, telegenic racers conspired to thrust Formula 1 in front of a new, desirable, and hitherto untapped audience that was:

Young(er)

Global

Aspirational and upwardly mobile if not yet wealthy

Naturally, those are just the sort of customers that luxury carmakers want to court.

Both Porsche and Audi entered the Formula 1 paddock and began shaking trees and taking clandestine meetings to see what teams might be available for either a financial partnership or an engine deal. Unlike the Andretti family, the German brands understood that Formula 1 would be operating a closed shop for the foreseeable future, so the way into the circus would be through an existing team. What were the options? Let’s take each team, listed in 2021 Constructors’ championship order.

Mercedes - Obviously a non-starter.

Red Bull - Successful team with first class facilities and personnel; Austrian owner Mateschitz is now 78 and has legacy ties to Porsche.

Ferrari - Even less likely than Mercedes.

McLaren - Rumored to have been for sale last year; Audi kicked the tires on both the Formula 1 team and the road car division.

Alpine (Renault) - Prideful team with big ambitions owned by a French automaker; no.

AlphaTauri - Red Bull “sister” team; located in Faenza, Italy.

Aston Martin - Lawrence Stroll is headstrong and determined, at least for now.

Williams - Owned by American PE firm Dorilton Capital; team leadership has legacy VW ties.

Alfa Romeo - AKA the Sauber team; all but confirmed that Audi will purchase Hinwil, Switzerland-based Sauber.

Haas - The American-flagged team operates under Ferrari’s wing.

So, that was a done deal and Porsche was going to enter Formula 1 either with Red Bull or Williams, right? And, given the choice, wouldn’t you prefer to join up with Red Bull?

After the Herbert Diess revelation in May and the Moroccan leak in July, the Formula 1 world waited … and waited for confirmation that the German brands would join the series.

Monterey Car Week falls annually during August, which is when Formula 1’s summer break takes place. Porsche debuted its new 911 GT3 RS during the event. The new GT3 RS features a ridiculously large rear wing that has an active aero element functioning like a Formula 1 car’s Drag Reduction System (DRS). I viewed the inclusion of the DRS terminology, which is apparently not a trademarked phrase, as a little dog whistle about Porsche’s impending Formula 1 announcement. Clearly, I was mistaken!

Porsche’s IPO: Timing, Structure & Pricing

I found another premonition of Porsche’s entrance into Formula 1 in an August 26, 2022 Bloomberg article previewing the IPO. Here are the key excerpts (emphasis mine):

Porsche has lined up investor interest for its initial public offering at a valuation of as much as $85 billion, signaling one of Europe’s biggest-ever listings is poised to go ahead despite market headwinds, according to people familiar with the matter.

Big-name investors including T Rowe Price Group Inc. and Qatar Investment Authority have already indicated interest in subscribing to the IPO in that valuation range, the people said. Porsche has also been gauging interest from billionaires including the founder of energy drink maker Red Bull, Dietrich Mateschitz, as well as LVMH Chairman Bernard Arnault, the people said.

On the same day, Audi formally announced it would enter Formula 1 in 2026. Still no news from Porsche…

The proposed structure of this IPO is fiendishly complex; far more so, in fact, than any IPO or other equity offering on which I have worked. That’s right, unlike anyone else who writes about cars from an enthusiast standpoint - whether for a paycheck or out of passion - I have worked on billions of dollars of capital raises, including numerous IPOs.

Further structure detail, courtesy of Bloomberg (emphasis mine):

The listed Porsche will have a dual share structure similar to Volkswagen with voting and non-voting shares. Porsche’s planned small free float and limited managerial independence - Porsche head Oliver Blume will carry on as chief executive officer of VW - has triggered governance concerns similar to criticism leveled at VW’s convoluted structure.

VW is selling 12.5% of total share capital, split into 25% of non-voting preference stock offered to outside investors, and 25% plus one share of common shares to Porsche SE. For the family company to fund the multi-billion-euro purchase, VW will pay out a special dividend.

The new setup will give the family the power to veto major strategic decisions at Porsche; since the takeover by VW, the brand has sometimes had to go along with moves that ended up being against its interests, such as a plan to build EVs with Audi at a plant in Hanover. Still, the two companies will remain closely linked to one another -- and to the German state of Lower Saxony, another major VW shareholder and home to VW’s largest factory.

A September 5, 2022 Bloomberg article relays Porsche executives’ posturing regarding market conditions (emphasis mine):

Volkswagen AG is pushing ahead with its plan to list a minority stake in the Porsche sports-car maker despite gyrating markets, paving the way for what could be one of Europe’s biggest initial public offerings.

The manufacturer is planning the initial public offering as early as this month, unless markets worsen significantly, VW said late Monday, targeting to finalize the listing by the end of the year. The move will direct funds to Europe’s biggest carmaker to foot the staggering cost of electrification and software development and return greater influence to the billionaire Porsche-Piech clan over the luxury automaker.

“We have shown a huge resilience especially in crisis times,” VW and Porsche Chief Executive Officer Oliver Blume said Tuesday on a call with reporters. “Looking back on the corona crisis, the semiconductor crisis, this year with the Ukraine conflict, we always have been able to show very high profit margins and we think this will be very convincing.”

On September 9, 2022, the Porsche-Red Bull Formula 1 deal officially died.

A September 13, 2022 Bloomberg article summarized a recent equity research note from HSBC that questioned Porsche’s mooted valuation:

Analysts at HSBC Holdings Plc poured cold water on the lofty valuations being assigned to Volkswagen AG’s Porsche unit ahead of a share sale by the sportscar-maker that’s set to be one of Europe’s biggest initial public offerings.

Porsche is worth between 44.5 billion euros ($45.1 billion) and 56.9 billion euros, analysts including Edoardo Spina said in a note. That’s lower than the 60 billion euros-to-85 billion euros ballpark being talked about in the media, they wrote.

HSBC’s model is based on comparing multiples with luxury vehicle rival Ferrari NV as well as German peers like Mercedes-Benz Group AG and Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, the analysts wrote. The analysts have removed Tesla Inc. from Porsche’s peer group as the US firm’s multiples reflect sales growth and software revenue potential that aren’t applicable to the German firm to the same degree.

Also on September 13, 2022, another Bloomberg article provided an update on Porsche’s IPO order book building (emphasis mine):

Volkswagen AG has lined up commitments from anchor investors including the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund as it pushes ahead with a listing of its Porsche AG unit, people with knowledge of the matter said.

Norges Bank Investment Management has agreed to buy stock in what’s set to be one of Europe’s largest initial public offerings, the people said. VW is discussing seeking a valuation of around 70 billion euros ($70 billion) to 85 billion euros, the people said, asking not to be identified because the information is private.

At the top end of that range, Porsche would be valued at almost as much as VW. Preference shares in Europe’s biggest carmaker have fallen by roughly 23% over the last 12 months, giving it a market value of 89 billion euros.

Other big-name investors like T Rowe Price Group Inc. have separately indicated interest in subscribing to the Porsche IPO, Bloomberg News reported last month. Qatar Investment Authority has made a preliminary commitment to buy a 4.99% stake, VW said this month.

Dietrich Mateschitz, the billionaire founder of energy drink brand Red Bull, also held talks about buying stock in the offering, the people said. However, he is no longer likely to proceed with an investment after the collapse of a potential Formula 1 partnership between Porsche and Red Bull, two of the people said.

A September 20, 2022 update from Bloomberg (emphasis mine):

Volkswagen AG garnered more than enough investor orders to cover the 9.4 billion-euro ($9.4 billion) initial public offering of its sports-car maker Porsche AG just hours after it started taking requests for the share sale, according to terms seen by Bloomberg.

The offer period for the German carmaker is likely to run until Sept. 28 and is open to investors in Germany, Austria, France, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. Four cornerstone investors -- Qatar Investment Authority, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, T. Rowe Price and ADQ -- have together committed to take up as much as 3.7 billion euros of the IPO.

Another equity research naysayer has their arguments summarized in a September 23, 2022 Bloomberg article (emphasis mine):

Porsche AG may be worth little more than two-thirds of the value being touted ahead of the luxury carmaker’s initial public offering, according to an analysis from Quest, a unit of Canaccord Genuity Ltd.

Volkswagen, the German group which owns the Porsche sports car brand, is seeking a valuation of 70 billion euros to 75 billion euros ($67.9 billion to $72.8 billion). But Quest analysts James Congdon and Veena Anand assessed Porsche’s equity value at between 48 billion and 50 billion euros.

The current IPO valuation range does not fully price current risks, Congdon and Anand told clients Friday. “Porsche’s customer demand is untested against rapidly rising interest rates and high inflation pressures.”

They added that their calculations had taken into account factors such as “weak corporate governance” and exposure to China.

So, to summarize Porsche’s IPO aspirations:

Porsche is pushing ahead with an IPO in exceptionally challenging market conditions, unless those market conditions worsen this week.

The transaction structure is Byzantine and rife with governance problems; the float will also be small.

Porsche has steadily walked its valuation expectations down over the month of September.

Dietrich Mateschitz is likely no longer purchasing Porsche shares.

Porsche’s side of the story tells you how things happened; Red Bull’s portion will explain why.

Red Bull, The World’s Greatest Racing Team

Red Bull Racing is the greatest racing team on the planet, and it’s difficult to argue otherwise. From the ashes of the disastrous Jaguar team, Red Bull has grown into a team that has managed to win titles in multiple different eras of Formula 1, an achievement no other team has matched in decades: Red Bull won both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ titles in each year of the 2010 - 2013 period, the last days of the naturally aspirated V-8 era; Red Bull won the Drivers’ title at the last gasp of the 2021 season, the final year of the “turbo hybrid” period; Red Bull will win both titles this year, unless a meteorite hits earth, in the first year of the new regulations that have comprehensively remade the sport’s aerodynamic approach. How did the outfit that Lewis Hamilton once referred to as “just a drinks company“ ascend to such an altitude?

Logically, we must take a detour through my childhood to set the stage.

By the time I had reached third grade, the lunchroom table discussion centered almost exclusively around video gaming consoles. Wanting to join the conversation with the other fellows, I asked for - and received - a Nintendo 64 for Christmas that year. I was only interested in automotive / racing games, however. I found myself augmenting my real-world Formula 1 knowledge with studious investigation of the F-1 World Grand Prix game.

I always played as Michael Schumacher, of course; I recall playing the game one evening, when I noticed that my Ferrari teammate was named “E. Irvine.” I reasoned, as a child might, that this was a corruption or misspelling of Ernie Irvan, the NASCAR racer. The only thing other than video games that merited discussion among my peers was NASCAR; we had already moved on from professional wrestling.

E. Irvine - that’s Edmund, or Eddie, Irvine, by the way - later joined the Jaguar team, which was formed when the Ford Motor Company purchased Jackie Stewart’s eponymous team and rebranded it. No less an eminence than Jacques Nasser, the CEO of the Ford Motor Company at the turn of the millennium, is said once to have asked aloud about the identity and pay packet of “Edmund Irvine,” who was then the highest paid employee in the FoMoCo galaxy. It is perhaps more forgivable for a child living in a backwater to struggle with Irvine’s identity than for his boss to profess ignorance.

This anecdote encapsulates Ford’s laughable management of the Jaguar team, which it put up for sale in 2004. Dietrich Mateschitz purchased the team and installed relative unknown Christian Horner to run the upstart operation. Mateschitz tapped his friend and countryman Dr. Helmut Marko, who raced in Formula 1 and won the 1971 24 Hours of Le Mans along with Gijs van Lennep in a Porsche 917, to serve as a team advisor. Marko had already been overseeing Red Bull’s trailblazing young driver development program.

Throughout its history, Red Bull has sought to compete against works entries while usually having a non-works engine / Power Unit. Red Bull used Cosworth engines, a legacy of the Stewart and Jaguar days in its first season - 2005; the team switched to Ferrari engines for the 2006 season before moving on to Renault power in 2007. Red Bull persisted as a Renault customer through the 2010 season before becoming the French automaker’s works partner from 2011, a relationship that would last through 2015, after which the relationship broke down in acrimonious fashion. The infighting began during the 2014 season, when Renault’s turbo hybrid Power Unit proved to be uncompetitive and unreliable in comparison to the dominant Mercedes offering. With limited options, Red Bull raced with a TAG Heuer-branded Renault from 2016 through 2018, just as McLaren had used a TAG Heuer-branded Porsche engine over 30 years prior! Red Bull switched to works Honda power for the 2019 season. Ever-fickle Honda announced at the end of 2020 its plan to depart Formula 1 after the 2021 season, ahead of the 2022 rule change.

Red Bull leadership, comprised of Team Principal Horner and advisor Marko, had grown tiresome of competing against the works teams without the assurance of works power. At the end of 2020, the two were focused on:

Ensuring their final year with Honda proved fruitful; Max Verstappen was overdue for a title fight, which would likely be against Lewis Hamilton and Mercedes.

Identifying a new, long-term engine solution; the options were slim:

Mercedes - Already supplying four teams; unwilling to supply to a top competitor.

Ferrari - Already supplying three teams; unwilling to supply to a top competitor.

Renault - Only supplying themselves, so eager for customers, but too much bad blood (on both sides).

Creating a fourth option - Either an internal program or a partnership with a new manufacturer.

Red Bull performed astonishingly well on both objectives: They won the 2021 Drivers’ title in the most dramatic fashion, just losing the Constructors’ title, and I believe they controlled and manipulated Formula 1’s Power Unit rule set for both the 2022 - 2025 period and the 2026 and beyond period to their advantage.

Red Bull Powertrains

Red Bull Powertrains, or RBPT, was established in 2021 and has hired a number of key personnel from competing Formula 1 works teams. RBPT took over from Honda on the Power Unit side for the 2022 season, although Honda remains involved to an extent, and there is a small Honda Racing Corporation (HRC) logo on the engine cover of both the Red Bull and AlphaTauri cars. The original plan was for HRC to provide support to RBPT for the 2022 and 2023 seasons, after which RBPT would be responsible for the Power Units. This agreement has subsequently been extended through to the end of 2025, which is when the current Power Unit regulations sunset. Crucially, and at the behest of Red Bull, the 2022 engine specs are generally frozen through 2025 - only “reliability” updates are allowed. This allowed Red Bull great flexibility in determining what it would do from 2026 onward: Either develop its own Power Unit in-house or partner with Porsche (or another manufacturer).

2026 Power Unit Regulations

Despite Formula 1’s popularity turnaround, the series has encountered challenges in attracting new manufacturers to provide Power Units. The turbo hybrid Power Units are profoundly complex, and the legacy participants have an extraordinary advantage given they have been racing them since 2014 (or 2015 in Honda’s case). Among the concessions to attract Audi and Porsche was an agreement to simplify and cheapen the Power Units, by omitting the MGU-H, as well as to develop more of the combined output from the electrical rather than engine side.

Obviously, these initiatives would also make it easier for Red Bull to develop its own competitive Power Units! Assuming, of course, that that was their goal all along.

The Artifice of The Red Bull-Porsche Deal

While Dietrich Mateschitz’s intentions are harder to parse, it is my belief that Red Bull’s leadership, specifically Horner and Marko, used Formula 1’s interest in Porsche’s potential entrance into the series, as well as Porsche’s own interest in that outcome, to advance Red Bull’s goals. The 2022 - 2025 Power Unit rule set is tailor made for Red Bull: They have secured an HRC-developed and supported Power Unit for all four seasons, and they don’t have to worry about further development. In the meantime, RBPT can develop their 2026 Power Unit, and they are already far enough along and confident enough in their abilities to thumb their nose at a potential OEM partner!

The cover story for the breakdown doesn’t ring true to me (emphasis mine):

Negotiations over a Red Bull-Porsche alliance from 2026 onwards were formally ended earlier this month as Porsche insisted on buying into Red Bull’s F1 operation and Red Bull held firm that all it would effectively accept was a glorified engine branding deal.

Red Bull’s unshakable confidence in its nascent Powertrains division is an impressively bold position to take given it is responsible for shunning a tie-up with a manufacturer of Porsche’s reputation.

The parties would not have been stuck negotiating the basic terms of a proposed deal if a near-term announcement were expected.

I can only conclude that Christian Horner and Dr. Helmut Marko used Porsche to their advantage, as a pawn, creating optionality and concessions that will help an independent Red Bull compete at the top of Formula 1 through the 2026 rule change and beyond.

Would you want to buy stock from the people who got played like a fiddle?